Addressing the Covid-19 Human Rights Abuses and Restoring Law and Order

From COVID-19 LAWLESSNESS by Willem Van Aardt

Listen to Dr Tess Lawrie’s reading of this post:

The World Council for Health is very pleased to publish this 5-page excerpt from Willem Van Aardt’s excellent book Covid-19 Lawlessness1. Willem Van Aardt (B.Proc, LL.M. PhD) is an International Human Rights and Constitutional Law specialist who resides in Barrington, Illinois, USA. He was admitted as an Attorney of the High Court of South Africa in 1996 and as a Solicitor of the Supreme Court of England and Wales in 2005. In 2020 he was appointed as an Extraordinary Research Fellow of North-West University Research Unit on Law, Justice and Sustainability. Willem is author of numerous peer-reviewed articles relating to the violation of fundamental human rights.

Over the past two years, millions of people across the West lost their jobs, were injured, and died as a direct or indirect result of illicit public policies that were implemented. Once the miscreant COVID-19 era bureaucrats have been ousted from their positions of power through lawful civil and political action, it is imperative to deal judiciously with the widespread human rights violations that occurred during the COVID-19 era.

The exhortation by Emily Oster in her October 21, 2022 article in “The Atlantic” to “Declare a Pandemic Amnesty” and forgive and forget what happened over the past two and a half years is not an appropriate nor reasonable course of action.38 Oster’s contention that any “misstep wasn’t nefarious. It was the result of uncertainty”, is simply not true.38 A group of corrupt supercilious political and corporate global elite willfully and lawlessly contravened International Human Rights Law (IHRL) and trampled on the dignity and human rights of millions of people in the pursuit of power and profit. In the interest of truth, justice, reparation, and non-recurrence these international criminals and their accomplices, that are the enemies of humanity, need to be investigated, prosecuted, and held to account in terms of the rule of law.

Although there is no standard model for dealing with the past (DWTP), the 2004 report of the UN Secretary-General on “The Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies” provides some guidance.25 The report determines that effective transitional justice strategies must be both inclusive in scope and all-encompassing in nature, involving all pertinent State actors and non-State actors in developing a “single nationally owned and led strategic plan.”26 The report further emphasizes that the practical definition of transitional justice should be expanded to include “judicial and non-judicial mechanisms, with differing levels of international involvement (or none at all) and individual prosecutions, reparations, truth-seeking, institutional reform, vetting and dismissals, or a combination thereof.”25

On December 16, 2005, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 60/147 entitled the “Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law.”27 Significantly, this document outlines the State’s obligations concerning gross violations of international human rights and humanitarian law. Principle 8 defines the term victim as:

…persons who individually or collectively suffered harm, including physical or mental injury, emotional suffering, economic loss or substantial impairment of their fundamental rights [and] also includes the immediate family or dependents of the direct victim and persons who have suffered harm in intervening to assist victims in distress or to prevent victimization.

The “Basic Principles and Guidelines” expand the rights offered to victims by combining entitlements allowed under both IHRL and international humanitarian law (IHL).25,26,27 In the 2006 case of DRC v Rwanda, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) affirmed the complimentary application of IHRL and IHL.29,30.

In 2006, 2007, and 2009 the UN Human Rights Council also addressed the issue of the “right to truth” in a series of studies, reports, and resolutions aimed at strengthening “the right to truth” as a principle of international law and a standalone fundamental right of the individual that should not be subject to limitations.31-33

In his 2010 article entitled “A Conceptual Framework for Dealing with the Past”, Jonathan Sisson proposes that the “Joinet/Orentlicher principles against impunity”, formulated by Louis Joinet (1997) and further refined by Diane Orentlichter (2005) at the behest of the Commission on Human Rights, and the right to truth principles, could be utilized as a framework for dealing with the past.25,34,35 Importantly, these principles are based on the IHRL concept of primary State responsibility to protect and respect fundamental human rights and the inherent right of remedy for individual victims of serious human rights infringements. As such, the principles do not involve new international or national judicial obligations but identify procedures and processes for the implementation of existing judicial obligations under IHRL.25

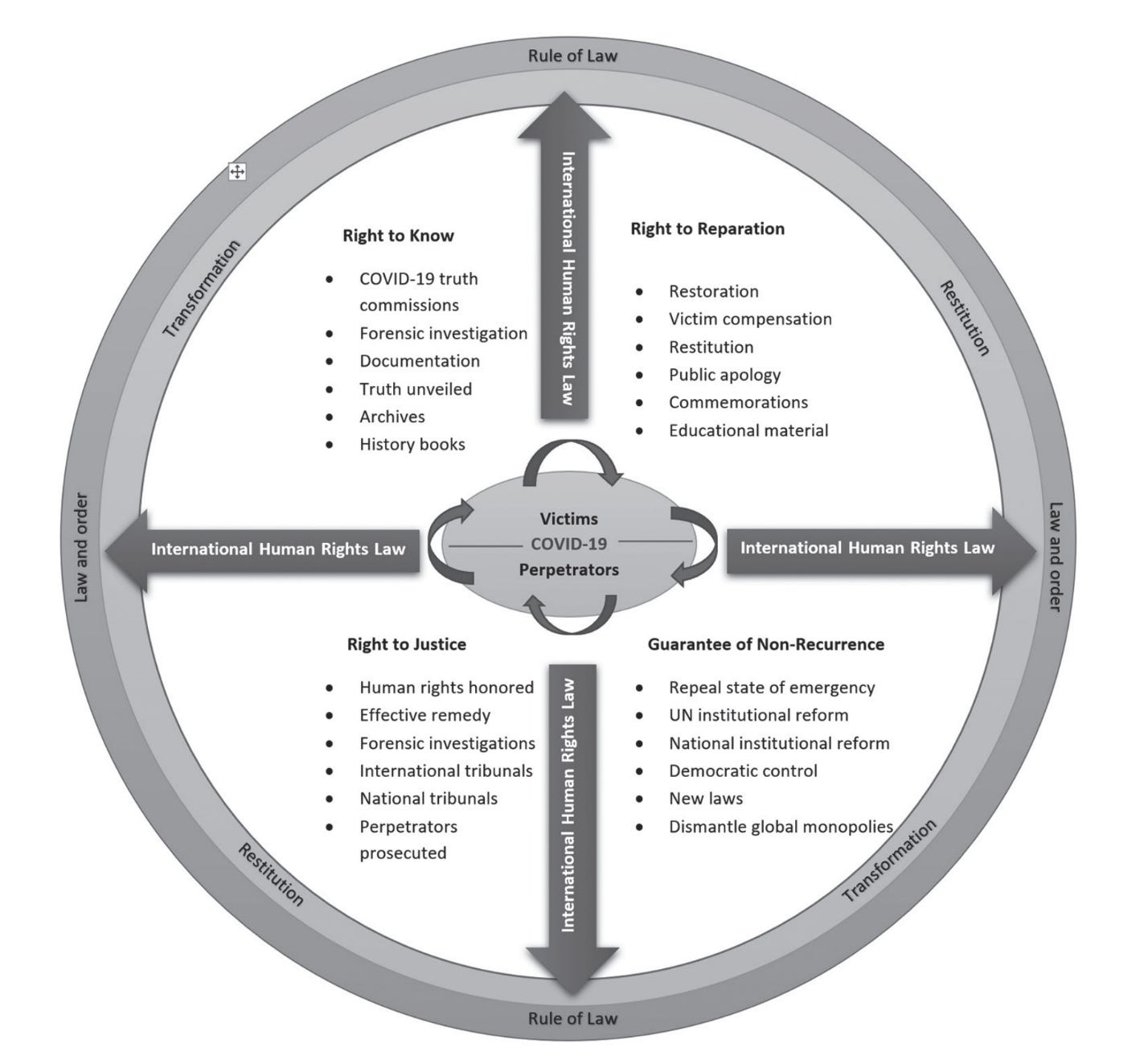

The “Joinet/Orentlicher” principles provide a helpful framework, from both a juridical and normative point of view, to deal with the insidious human rights violations that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. The principles identify four critical rights for juridically dealing with the past: i.) the right to know, ii.) the right to justice, iii.) the right to reparation, and iv.) the guarantee of non-recurrence.25

i. The Right to Know – The right of victims, their families and of the public at large to know the truth and the duty of the State to conserve remembrance.25 The Right to Know includes the right on the part of specific victims of human rights violations and their families to learn the truth about what happened to them or their loved ones, in particular with respect to severe injuries and death due to mandatory COVID-19 vaccination policies.25 It is based on the right on the part of the public at large to know the truth about the circumstances, decisions, and actions that led to the commission of widespread and systematic human rights violations in order to avoid their recurrence. In addition, the right to know obligates the State to undertake measures to conserve the collective memory from extinction, such as securing archives and other evidence, to shield against the advancement of similar inhumane public policies in the future. To ensure this right, quasi-judicial commissions of inquiry (in practice, often called “truth” commissions) should be established. Given the prevalent human rights abuses relating to COVID-19, both national and international “COVID-19 Truth Commissions” should be established. The commissions would serve a twofold purpose: 1) to disassemble the State and non-State machinery and institutions that facilitated and orchestrated the human rights violations to ensure that they do not recur; and 2) to gather, archive, and preserve evidence of serious human rights infringements for the judiciary to utilize in subsequent civil and criminal prosecutions.25

ii. The Right to Justice – The right of victims to a fair legal remedy and the duty of the State to investigate, indict, and duly punish the criminals.25 The Right to Justice means that any victim can claim their fundamental human rights and get a reasonable and effective remedy, including the expectation that those responsible will be held legally liable in line with the doctrine of versari in re illicita and that damages will be paid.25 The right to justice also involves legal obligations on the part of the State to investigate human rights violations, arrest and prosecute the offenders and, if their guilt is proven, punish them. The politicians, public officials, corporations, and public figures who contravened jus cogens norms and defrauded the public with false claims of safety and efficacy should be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. The super-profits made directly and indirectly by various corporations that propagated false narratives and contravened bedrock human rights norms should be forfeited and recuperated through heavy penalties and utilized to compensate victims and restore law and order. National courts have primary responsibility, but international criminal tribunals may exercise concurrent jurisdiction if needed. The right to justice further imposes restrictions on amnesty, asylum, extradition, non bis in idem, due obedience, official immunity, prescription, and other measures, insofar as they may be exploited to obstruct justice and shield the perpetrators from prosecution.25

iii. The Right to Reparation – The right of specific victims or their children and relatives to reparation and the duty of the State to provide satisfaction.25 The Right to Reparation necessitates remedial measures for individual victims or their dependents or relatives. This includes the duty to restore the victim to their previous situation,25 - for instance, reappointing citizens who lost their jobs due to the vaccine mandates and compensating those families whose breadwinners died or were disabled. It further entails monetary compensation for mental or physical injury, medical care, including physiotherapy and psychological treatment, moral damage due to defamation, lost career opportunities, education, social benefits, legal expenses, and other expert assistance to enforce fundamental human rights. The duty to provide satisfaction relates to communal measures of reparation. These entail symbolic actions, such as an annual tribute to the COVID-19 victims of mass mandatory vaccination policies and building remembrance memorials and museums. It further consists of the acknowledgment by the State of its accountability in the form of a public apology (to help to restore victims’ dignity) and the inclusion of a truthful account of the biomedical human rights violations that occurred during the COVID-19 era in all public educational materials at all levels.

iv. The Guarantee of Non-Recurrence – The right of victims and the public at large to be safeguarded from further abuses and the duty of the State to ensure the rule of law.25 The Guarantee of Non-Recurrence centers on the need to remove senior government officials from office who are implicated in serious human rights violations, to fundamentally reform or disband the various corrupt government and non-government institutions that facilitated the human rights violations, and to repeal state of emergency laws and regulations. It further requires reforming laws and State institutions in accordance with the norms of IHRL and the rule of law. In particular, the reform of global and national public health agencies, judicial bodies responsible for the protection of fundamental human rights, and the eradication of conflicts of interest should be a priority. The screening of senior public officials must comply with the requirements of the rule of law and the principles of meritocracy, non-discrimination, and complete transparency. All public officials with conflicts of interest and those who breached IHRL and their fiduciary duties to the public during the COVID-19 pandemic should be removed from their positions and prosecuted. The funding structures of global and national public health organizations, major academic institutions, and high-impact academic journals should be reformed to eliminate undue political and corporate influence. Of particular importance is the enactment of more robust competition and anti-monopoly regulations and the dismantling of the global pharma, global technology, global social media, global mainstream media, and global financial monopolies that played a key role in the human rights defilements during the pandemic. The judiciary’s independence should be strengthened and reintroduced to hold politicians, public officials, powerful corporations, and their elite owners accountable.25

Figure 13.1, adapted from a design by Swiss Peace, a division of Human Security of the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, illustrates some of the main mechanisms and procedures associated with the four principles above.25

Dealing with a culture of human rights abuses is one of the most complex tasks facing citizens in transitioning from inherently fascist forms of government to true democratic forms of administration that protect and respect fundamental human rights.25 The “principles of international law recognized in the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal and in the judgment of the Tribunal” adopted by the International Law Commission in 1950 specifically determine:

i. Crimes against international law are committed by men, not abstract entities, and only by punishing individuals who commit such crimes can the provisions of international law be enforced.

ii. Criminal liability exists under international law even if domestic law does not punish an act that is an international crime.

iii. The principle of international law, which under certain circumstances, protects the representatives of a state, cannot be applied to acts that are condemned as criminal by international law. The authors of these acts cannot shelter themselves behind their official position in order to be freed from punishment in appropriate proceedings.

iv. The fact that a person acted pursuant to order of his Government or of a superior does not relieve him from responsibility under international law, provided a moral choice was in fact possible to him.36,37

To restore confidence and accountability in the world, it is necessary to admit publicly the gross abuses that have taken place during the COVID-19 pandemic and to hold those responsible and liable who have committed, planned, ordered, executed, and profited from such abuses, and to compensate victims. This process of dealing with the past is an essential prerequisite for re-establishing the rule of law.25

Chapter 13 References 25 - 38

……..

……..

25. Sisson, J. (2010). “A conceptual framework for dealing with the past.” Politorbis 50, no. 3 (2010): 11-15.

26. United Nations. (2004). Report of the UN Secretary General on the Rule of Law and Transitional Justice in Conflict and Post-Conflict Societies (S/2004/616), p. 9.

27. UN General Assembly. (2005). Resolution 60/147, 16 December 2005

28. Bassiouni, M. C. (2006). “International Recognition of Victims’ Rights”. Human Rights Law Review. 6 (2): p. 204–5. 29. CJ Judgments. (2006). “(DRC v Rwanda).[2006] ICJ Rep 6”

30. van Boven, T (2006). Freshman; et al. (eds.). ‘Victims’ Rights to a Remedy and Reparation (PDF). Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV. p. 19–40.

31. Commission on Human Rights. (2006). Sixty-second session Item 17. Study on the right to the truth Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights E/CN.4/2006/91 8 February 2006.

32. Human Rights Council. (2007). IMPLEMENTATION OF GENERAL ASSEMBLY RESOLUTION 60/251 OF 15 MARCH 2006 ENTITLED “HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL” Right to the truth Report of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights A/HRC/5/7. 7 June 2007.

33. Human Rights Council. (2009).ANNUAL REPORT OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS AND REPORTS OF THE OFFICE OF THE HIGH COMMISSIONER AND THE SECRETARY-GENERAL Right to the truth Report of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights* A/HRC/12/19. 21 August 2009.

34. Commission on Human Rights. (1997). THE ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE AND THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF DETAINEES. Question of the impunity of perpetrators of human rights violations (civil and political). Revised final report prepared by Mr. Joinet pursuant to Sub-Commission decision 1996/119. E/CN.4/ Sub.2/1997/20/Rev.1. 2 October 1997.

35. Commission on Human Rights. (2005). PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS Impunity `Report of the independent expert to update the Set of principles to combat impunity, Diane Orentlicher* Addendum Updated Set of principles for the protection and promotion of human rights through action to combat impunity E/CN.4/2005/102/Add.1. 8 February 2005.

36. UN General Assembly. (1950). Affirmation of the Principles of International Law recognized by the Charter of the Nürnberg Tribunal, 11 December 1946. Available at: https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draft_articles/7_1_1950.pdf (Accessed: October 9, 2022).

37. Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal, vol. I, Nürnberg 1947, page 222-224.

38. Oster, E. (2022) Let’s declare a pandemic amnesty. The Atlantic. Available at: www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/10/covid-response-forgiveness/671879/ (Accessed: November 4, 2022).

….

……

Please help support our work!

If you find value in this Substack and have the means, please consider making a donation to support the World Council for Health. Thank you.

Can’t donate but would like to contribute? We’re always looking for volunteers, so get in touch!

Van Aardt, Willem. (2022) “COVID-19 Lawlessness- How the Vaccine Mandates, Mask Mandates and the perpetual State of Emergency, are unethical and unlawful in terms of Natural Law, the Social Contract and modern International Human Rights Law” P 355 -361 Mallard Publications, Chicago

Praying the day comes when they're all held accountable. 🙏

I agree that something needs to be done. Yet, using guidelines that come from the United Nation on human rights is very curious. The reason that I say this because they take responsibility for what is happening now. Their counterpart the World Health Organization is in deep with covid and the exaggerated environmental crisis. The wrongdoers should be hels responsible, yet the how is the question.